Influence: The Beauty of Impermanence

Occasionally we discuss philosophical concepts that have motivated Japanese craftsmen for centuries, such as wabi-sabi. In this post, we consider the artistic value of impermanence.

It's hard to look forward to an expiration date. It's a period that prevents thought of what follows, a push to let go of something that you once held dear. The words that we use to talk about ending make it almost impossible to see anything good in the process. Terms like 'obsolete,' 'worn out' or 'finished' focus only on the tragedy of immediate loss. They reflect and shape our mindset; we may be aware that a piece of clothing, for instance, will not hold up forever but we do all that we can to minimize that eventual end. We look for things that will endure and count them as valuable, while quietly discarding that which isn't useful anymore.

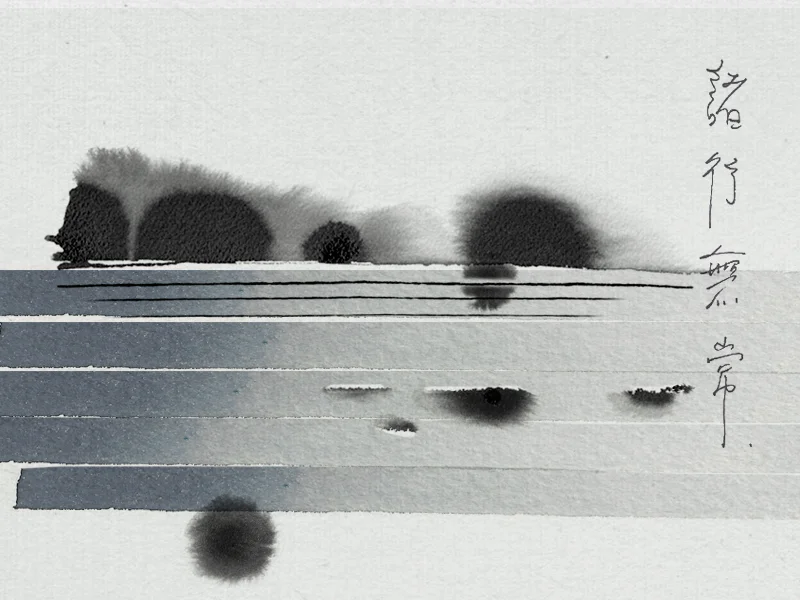

In Japan, by contrast, over a thousand years of Buddhist history has led to an awareness and acceptance of the inevitable decline inherent in our universe. The phrase 諸行無常, for instance, means “all things don't last” but is commonly understood as more than a cosmic expiration date; those four characters are intended to mold present actions in view of the coming end. Much of Japan's art and literature was made with an eye to this truth.

「行く河の流れは絶えずして、しかももとの水にあらず。淀みに浮かぶ泡沫は、かつ消え、かつ結びて、久しくとどまりたる例なし。世の中にある人と柄と、またかくのごとし。」鴨長明、『方丈記』

“The moving river never stops flowing and is not the same water as before. The bubbles that come to the surface in still pools sometimes disappear and sometimes gather, but none lasts for long. All the people in this world and their habitations are just like these.”

– Kamo no Chōmei, An Account of My Hut

It is easy for this sort of reflection to become melancholy, a mere lament for what we cannot change. However, the creative drive of many traditional Japanese crafts has come from using natural processes—age, weathering, wear after use— as another technique in the making process. Many ceramic kilns are wood-fired, which leads to variable temperature and affects the glaze unevenly, just so this random element of imprecision can give each piece an idiosyncratic stamp. Artisans also make their wares with an eye to savoring change in the future; patinas in bronze ware, for example, are not polished away but embraced as an integral and unique feature of each piece.

Letting go of permanence lets us savor the delight of the present, enjoying what the piece or experience has to say to us right now. If we see it again, it has changed and so have we. Complete permanence is impossible in this world; any attempt represents only a frozen memory, not an active life. By accepting this truth, we can better endure and possibly even enjoy its gradual fade rather than attempt to fight time to preserve it. Perhaps there is something freeing in knowing that an end is coming, and harnessing that natural change into our own creative process.

WORDS BY KYLAN SCHROEDER

ARTWORK BY JENNY NIEH