Legacy: Life of Antonin Raymond

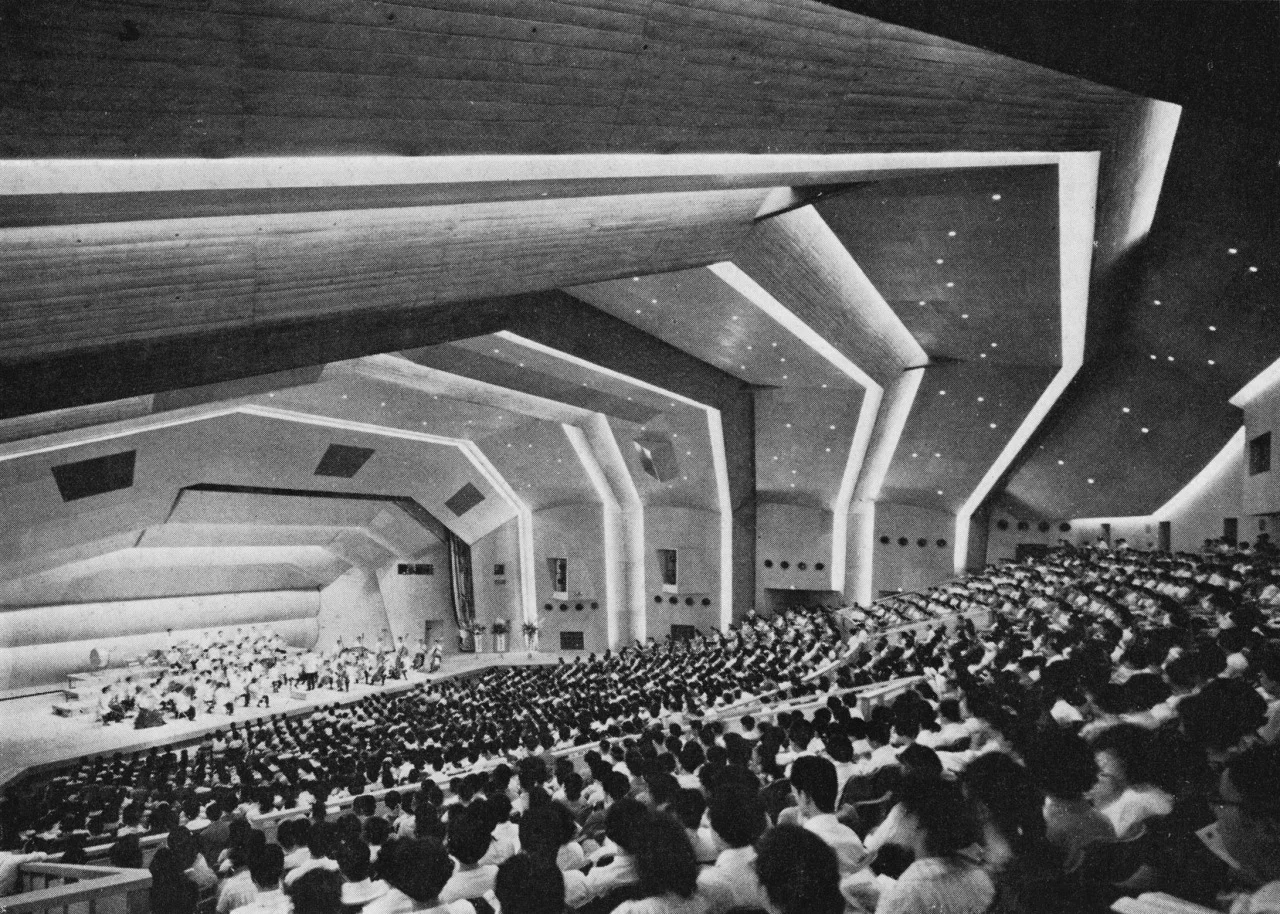

Antonin Raymond and L.L. Rado, Gunma Music Center, 1961. Takasaki, Japan.

When it comes to creating a legacy, architects are uniquely situated. After all, what other job requires your projects to outlive you? Who else can shape raw materials into palaces, universities, and other stages of daily life? As artists, architects combine art and mathematics into a physical living space. As engineers, they envision rooms, offices and foyers to ease and shape modern life. A truly great architect, however, reflects the spirit of his era in his work while ensuring that his building never fades into irrelevance. On all these fronts, the work of Antonin Raymond leaves behind an inimitable legacy.

Czech-born and American-trained, Raymond spent years in Japan producing projects that bridged cultures as well as architectural styles. His Tokyo buildings include St. Anselm's Church, the Reader's Digest offices, and, in partnership with Frank Lloyd Wright, the Imperial Hotel. Raymond specialized in exposed concrete buildings, marveling at the care his Japanese artisans took when handling the material. In simple, ordinary materials like concrete Raymond saw possibilities that great contemporaries like Wright ignored. Today, exposed concrete has become a key Japanese architectural detail, and he is remembered as one of the fathers of modern architecture in Japan.

For Raymond, the key to successfully combining traditional Japanese and modern architecture was in the "wise handling of materials that speak to us."* Natural materials like wood, alongside modern materials like concrete, could give voice to new textures and details. In a similar way, he was in a unique position to combine the two cultures he identified within himself--Western and Japanese--and channel their strengths towards something greater. While living in Japan, Raymond’s outsider status gave him a gift for respectfully synthesizing the underlying values of foreign cultures and reflecting them into his projects. His work and its reception illustrates how unity between contrasting cultures can fuel true innovation.

As the post-modernist movement began to take shape around him, Raymond believed that Japanese architecture would not develop in the same way as the West, but rather remain a pure, uncompromising example of what architecture should be in an ideal world. In Raymond's mind, the simplicity upheld by Japan's culture could circumvent the growing excesses of industrialization and materialism. He saw Japan as an adaptive culture: in a 1922 essay for Trans-Pacific Magazine, Raymond envisioned Japanese artisans rebuilding their country using reinforced concrete, harnessing its unique artisan expertise to explore new possibilities in form. Japan could uphold its legacy by running ahead into the future, protecting its architectural identity while also innovating beyond anyone's expectations.

Though not as well-known as Frank Lloyd Wright or Le Corbusier, Antonin Raymond’s work started a global interest in honest construction. His lifework shows how every aspect of architecture, from minute details to overall form, becomes a total work of art when it reflects the needs of daily life. His life provides a unique window into the diverse and ongoing relationship between Japan and the United States. Though his work is founded on traditionalism, Raymond's cross-cultural legacy is entirely modern.

"A true designer tries every moment of his existence to rid himself of his own personality, to conceive and create things in an impersonal way. He believes that personal opinion is wrong and is nothing but a bundle of idiosyncrasies. He designs according to definite and age-long principles." - No Place for Personality, Antonin Raymond, 1953

*Crafting a Modern World: The Architecture and Design of Antonin and Noemi Raymond

WORDS BY MAGALI ROMAN