Wabi Sabi and the Art of Imperfection

An immaculate white wall, cracked paint peeling from its corners. A swept sidewalk covered in patches of moss. A delicate porcelain vase with a small crack by its base. An evening garden, the first scattered leaves of the autumn season resting on the lawn. The Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, in its purest, most idealized form, is precisely about these delicate traces, this faint evidence of human life at the borders of nothingness. It is sight that is attained by learning to see the invisible beauty innate in everyday life. Its definition is as solid as fog, its meaning as fluid as water.

The term dates back to the early 16th century, when Japanese monks began performing tea ceremonies with humble utensils in a reaction to the ornately refined Chinese aesthetic that was popular at the time. This reactionary movement began to foster the idea that an object, an act, or a word could be beautiful even with its imperfections. Wabi (侘) is a philosophical construct: the inward, subjective way of life. Sabi (寂) is an aesthetic construct rooted in a given object and its features: material objects, art, and literature. Brought together, the concept fosters an aesthetic ideal of the quiet and sensitive state of mind that is an elemental part of Japanese culture. Artist and anthropologist Leonard Koren, calls it "the most conspicuous and characteristic feature of traditional Japanese beauty, occupying roughly the same position in the Japanese pantheon of aesthetic values as the Greek ideals of beauty and perfection in the West.”

In practice, objects that exhibit wabi-sabi qualities are made in a way that explore the human effort, and thus expose the fragility of man. In the Western sphere this most closely resembles a rustic aesthetic: earthy, unpretentious objects handcrafted from natural materials. In sharp contrast to modern, sleek, mass-produced culture, wabi-sabi is laden with imperfections. Pottery in the wabi-sabi style may have irregular edges or uneven glazing. It is that imperfection that reveals the human behind the object, the soul behind the work, the rawness in artistry.

To discover wabi-sabi is to see the singular beauty in something that may first look not very beautiful at all. To architect Mark Jensen, wabi-sabi is a “resistance to a world with a short attention span, ruled by the viral, the decorative and the commodifiable.” The eyes of modern society more and more push us toward an ideal perfection: the spotless Instagram post, the perfect career, the immaculate life. In times like these, wabi-sabi reminds us that imperfections are marks of authentic humanity: something to revere, not discourage. In order to see true essence, this imperfect perfection, one must look beyond the obvious--one must look within.

WORDS BY MAGALI ROMAN

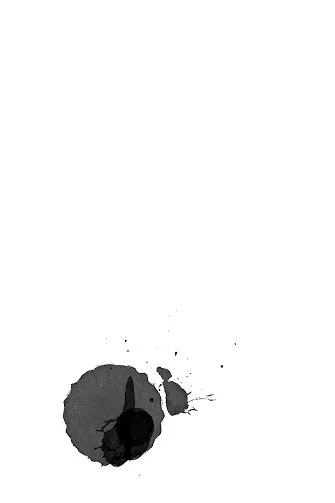

ARTWORK BY JENNY NIEH